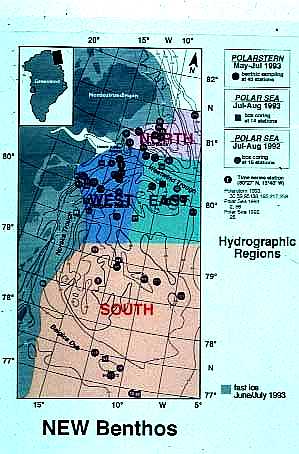

Perennial ice cover and a restricted growing season have lead to

the misimpression that the Arctic Ocean and its shelves are biological deserts.

We now know that some

Perennial ice cover and a restricted growing season have lead to

the misimpression that the Arctic Ocean and its shelves are biological deserts.

We now know that some Arctic shelves have very high rates of primary production and that the

Arctic Ocean is a site of active carbon cycling. In some areas, much of

this production falls unconsumed to the bottom, such that the water column

and benthic processes appear to be particularly tightly coupled.

Arctic shelves have very high rates of primary production and that the

Arctic Ocean is a site of active carbon cycling. In some areas, much of

this production falls unconsumed to the bottom, such that the water column

and benthic processes appear to be particularly tightly coupled.

location,

seasonal characteristics, and recurring nature, polynyas may represent

the best location to investigate the coupling between water column characteristics

and benthic community structure.

location,

seasonal characteristics, and recurring nature, polynyas may represent

the best location to investigate the coupling between water column characteristics

and benthic community structure.

an ideal system in which to test whether a compressed season

of pelagic productivity corresponds to recruitment patterns in benthic

organisms.

an ideal system in which to test whether a compressed season

of pelagic productivity corresponds to recruitment patterns in benthic

organisms. Many continental margins are sediment-starved and dominated

by hardbottoms. From a biological perspective, these hardbottoms are important

benthic habitat because they provide extensive substrate for plant and

animal communities. From a geological perspective,

Many continental margins are sediment-starved and dominated

by hardbottoms. From a biological perspective, these hardbottoms are important

benthic habitat because they provide extensive substrate for plant and

animal communities. From a geological perspective,

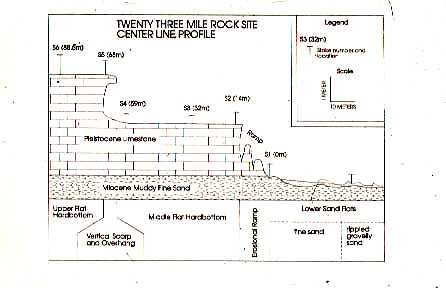

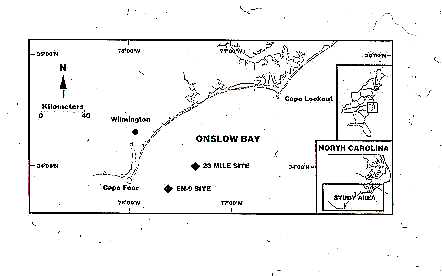

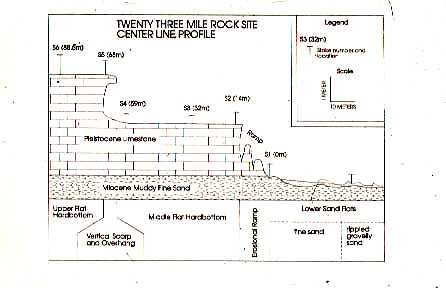

sediment-starved shelf

systems form modern condensed sections which are important components of

many stratigraphic models because they identify episdes of sediment starvation

during high stands of sea level. In collaboration with geologists from

East Carolina Univesity and North Carolina State, I examined the relationships

between hardbottom morphology, benthic community structure, and storms.

sediment-starved shelf

systems form modern condensed sections which are important components of

many stratigraphic models because they identify episdes of sediment starvation

during high stands of sea level. In collaboration with geologists from

East Carolina Univesity and North Carolina State, I examined the relationships

between hardbottom morphology, benthic community structure, and storms.

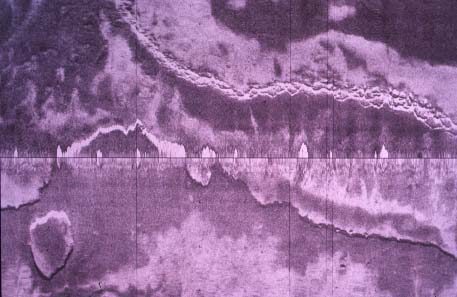

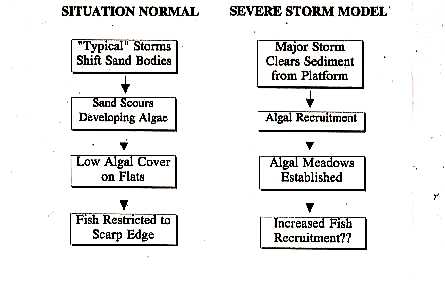

These relationships were examined using sidescan

sonar, high resolution seismic profiling, video and still photography,

vibracores and hydraulic rock drill cores, observations from submersible

and diving, and manipulative experiments. Hardbottom habitats proved to

be dynamic with changes on time scales from days to years in reaction to

These relationships were examined using sidescan

sonar, high resolution seismic profiling, video and still photography,

vibracores and hydraulic rock drill cores, observations from submersible

and diving, and manipulative experiments. Hardbottom habitats proved to

be dynamic with changes on time scales from days to years in reaction to

a complex set of inter-related processes: 1) bioerosion of pre-existing

stratigraphic units, 2) individual storms and seasonal storm patterns modifying

the distribution of surficial sands, and 3) effect of sand distribution

on benthic community structure.

a complex set of inter-related processes: 1) bioerosion of pre-existing

stratigraphic units, 2) individual storms and seasonal storm patterns modifying

the distribution of surficial sands, and 3) effect of sand distribution

on benthic community structure.

In Maine, 3 commercially important species co-occur on intertidal mud and sand flats: Mya arenaria (soft-shelled clam) and the polychaete worms Glycera dibranchiata (blood worm) and Nereis virens (sand worm). In Maine in 1996, soft-shelled clams ranked 4th in landed value among marine species and both worms together ranked 14th. All three species are harvested using hoes with 4-6 tines that vary in length from 20-30. Clams are consumed while worms are used for bait in recreational fisheries. Harvesting soft-shelled clams with a hoe results in the breakage and death of some clams. Up to 20 % of commercial-sized may be broken during digging. Although worm diggers also use hoes and turnover sediment, there has been no assessment of damage to clams by worm digging

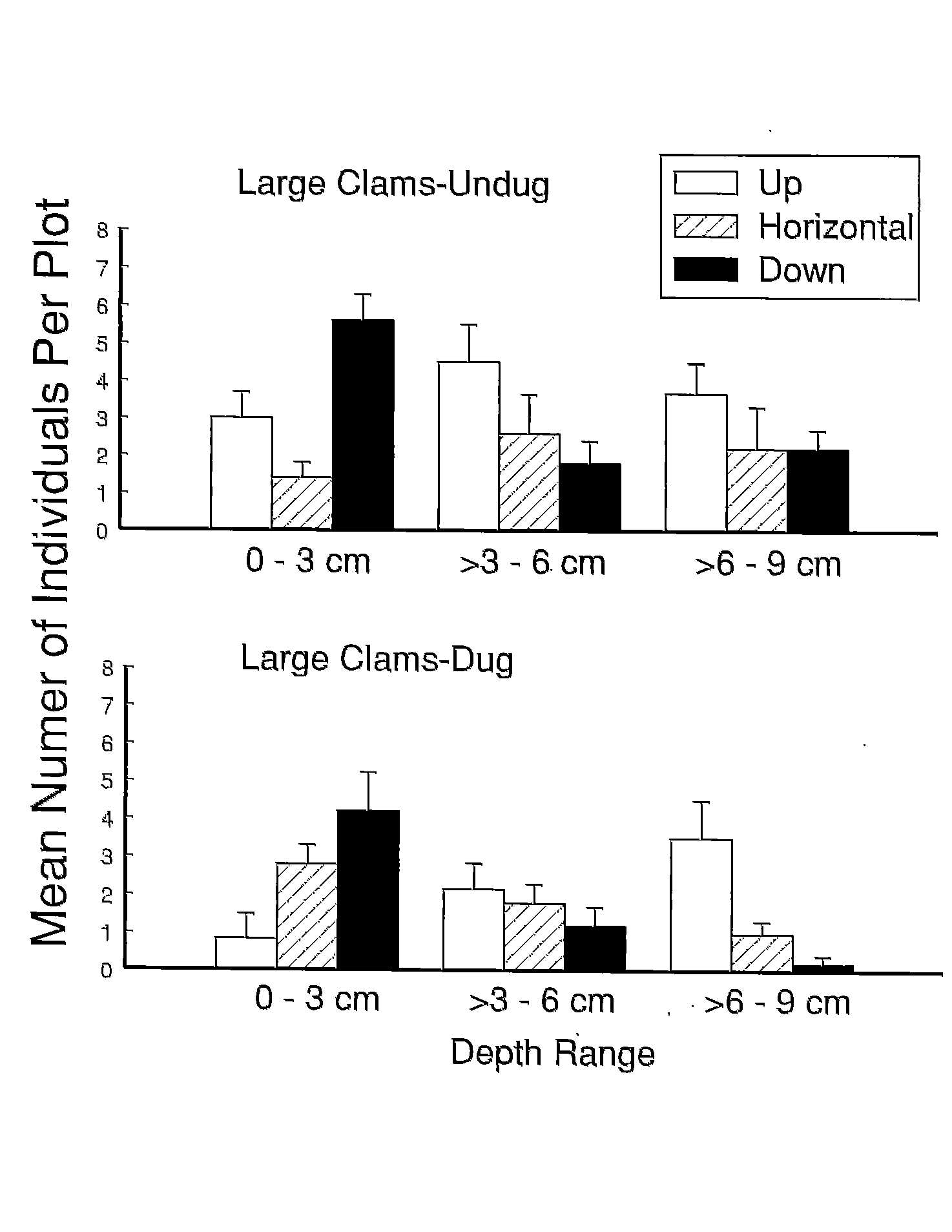

In addition to crushing or breaking shells, worm digging (and clam digging) can effect the survival of clams by displacing them from their natural living depth in the sediment. Turning over the sediment can either bury clams deeper than they normally live or expose them on the sediment surface. When suffocation and exposure are included as sources of mortality, up to 50% of the individuals remaining after clam harvesting may. Clam burial experiments clearly show that clam survival declines with increased burial depth. The ability of clams to survive burial and re-establish their normal living depth is dependent on the position in which they are buried (upright, horizontal, down), clam size, and sediment type.

Exposure of clams on the sediment surface increases their chances of freezing or desiccating and greatly increases their susceptibility to avian predators during low tide and demersal fish and crustacean predators during high tide. Small clams rebury faster than large clams. Most larger clams (shell length greater than 6 cm) require more than 10 hours to rebury and in some experiments many did not manage to rebury even after 48 hours. In these experiments, clams were either placed in a horizontal position on the sediment surface or their orientation was haphazard. Yet, clams exposed by digging are found on the sediment surface in all orientations and orientation is likely to have a profound effect on reburial rate because Mya reburies by pulling itself into the sediment with the strong muscle located at its pedal opening. When the anterior edge of the shell is not in contact with the sediment surface, clams can not rebury efficiently. Reburial rate is also dependent on sediment type and none of the studies examining reburial were conducted in the field with natural sediment conditions. Furthermore, sediment consolidation on digging tailings is very different than on undug sediment and might effect rates of reburial.

In Maine, clam and worm diggers often find themselves digging next to each other and conflicts between the two fisheries date back to the 1950s. The impact of worm digging on clam populations is a heated topic today but only one study has addressed the effects of worm digging on Mya populations in Maine. Brian Beal examined the effects of blood worm and clam digging on the survival and growth of cultured and wild juveniles (average shell length 12.5 mm) of Mya. He found that predation effects during the summer, when his experiment was conducted, masked any effects of digging on the survival of juveniles. Only when clams were protected from predators was an effect of digging on survival detected, and that effect was positive. Beal's experiment, though important, does not address the effects of digging on larger individuals (greater than 35 mm shell length) which have reached a size/depth refuge from most predators.

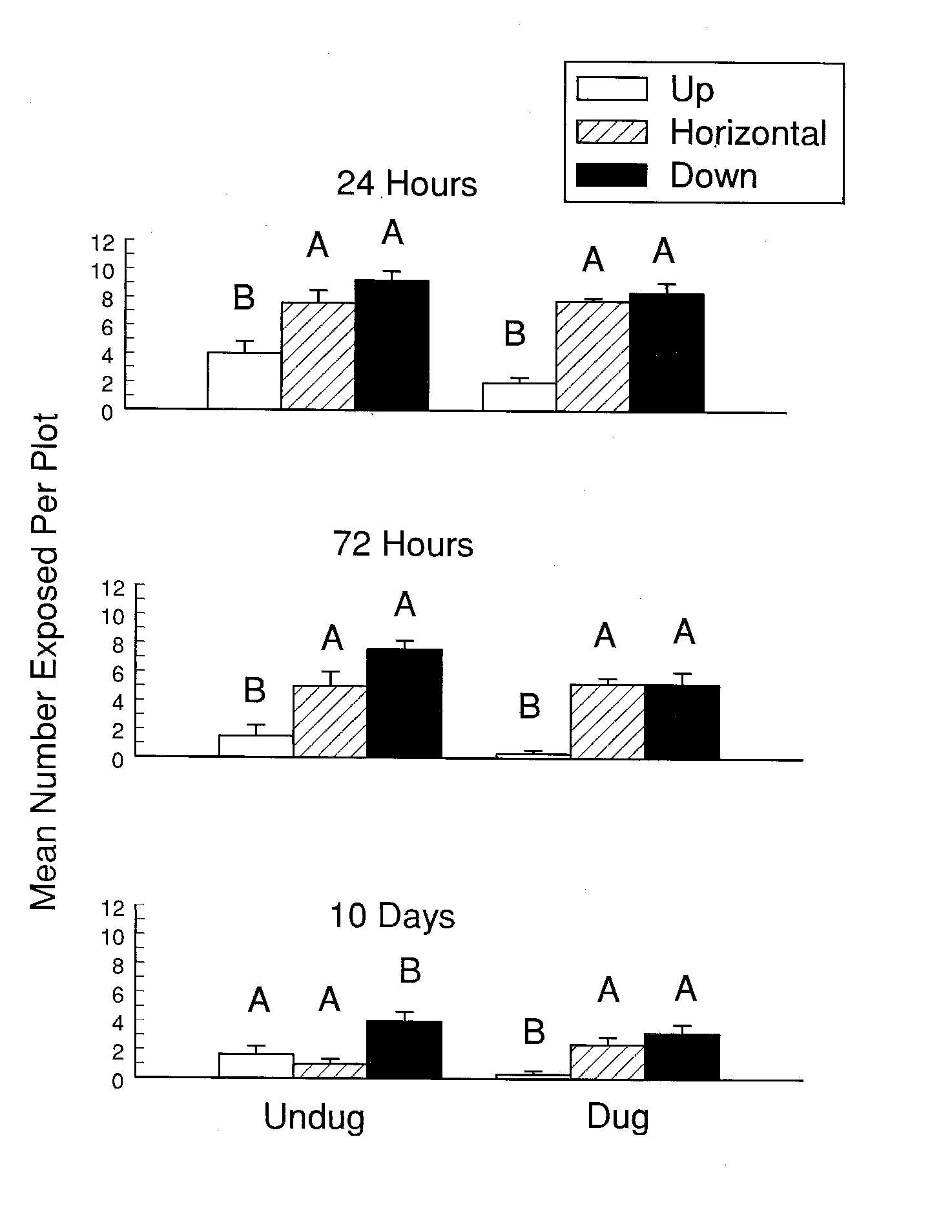

I conducted experiments to determine the direct and indirect effects of

blood worm (Glycera dibranchiata) digging on the soft-shelled clam, Mya

arenaria. About 6% of the clam population are exposed on the sediment

surface during each turn over of the sediment by worm diggers. Over twenty

percent (22.2%) of the clams exposed had at least one valve damaged. Of

intact clams exposed, 15.2% were found with their siphon up, 41.1% with

their siphon down, and 43.7% were horizontal on the sediment surface. After

72 hours, all small clams (<3.5 cm shell length) had reburied while 37% of

the large clams (>5 cm) remained exposed. Even after 13 days, 19% of large

clams placed on recently dug sediment and 25% of clams on undug sediment

remained exposed. Both large and small clams placed in the vertical

position reburied quicker and to greater depths than those in the

horizontal or inverted positions. There was no difference in reburial rates

between clams exposed on undug and recently dug sediment. Recovery of large

clams, however, was much greater (96.2%) from undug sediment than dug

sediment (63.1%) and twice as many clam shells exhibiting evidence of

predation were recovered from the dug than the undug area.

I conducted experiments to determine the direct and indirect effects of

blood worm (Glycera dibranchiata) digging on the soft-shelled clam, Mya

arenaria. About 6% of the clam population are exposed on the sediment

surface during each turn over of the sediment by worm diggers. Over twenty

percent (22.2%) of the clams exposed had at least one valve damaged. Of

intact clams exposed, 15.2% were found with their siphon up, 41.1% with

their siphon down, and 43.7% were horizontal on the sediment surface. After

72 hours, all small clams (<3.5 cm shell length) had reburied while 37% of

the large clams (>5 cm) remained exposed. Even after 13 days, 19% of large

clams placed on recently dug sediment and 25% of clams on undug sediment

remained exposed. Both large and small clams placed in the vertical

position reburied quicker and to greater depths than those in the

horizontal or inverted positions. There was no difference in reburial rates

between clams exposed on undug and recently dug sediment. Recovery of large

clams, however, was much greater (96.2%) from undug sediment than dug

sediment (63.1%) and twice as many clam shells exhibiting evidence of

predation were recovered from the dug than the undug area.

These results suggest that a significant portion of the large, commercial sized clams exposed during worm digging will not survive to rebury. The experiments at Maquoit Bay were conducted during October and November when air temperature is lower and predators less abundant than during the summer. Clams might rebury quicker at temperatures higher than those recorded during our experiments (16° C), but exposure during just one low tide during the summer is likely to make them prey for epibenthic predators. Even in the fall, predators probably removed upwards of 40% of large clams exposed on recently dug sediment. During the summer, exposed clams will also have a higher risk of dying from desiccation than during the fall.

Many of the clams that reburied, particularly those which were exposed

with their siphons down or in the horizontal position, buried to shallower

depths than they are normally found. These shallow-dwelling clams will be

more susceptible to predation than individuals living deeper in the sediment.

Many of the clams that reburied, particularly those which were exposed

with their siphons down or in the horizontal position, buried to shallower

depths than they are normally found. These shallow-dwelling clams will be

more susceptible to predation than individuals living deeper in the sediment.

Most flats in Maine, and Maquoit Bay is no exception, are dug repeatedly

for worms during a year. Repeatedly exposing clams to predation and

desiccation will affect their survivorship and the energy expended in

continually reburying may effect clam growth and reproduction. The effects

of repeated digging on clam populations are not known. Without further

study it is impossible to estimate how often a flat can be dug for worms

without impacting the clam population. Furthermore, the percent of the clam

population damaged or exposed undamaged on the sediment surface by digging

may vary due to differences in sediment, density of clams, digging styles

and structure of worm hoes.