In a first-ever Bates trip to Cuba, students find a study in contradiction

By Avi Chomsky, assistant professor of history

Photography by Mariano Pelliza '96

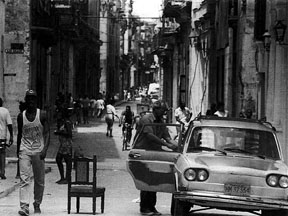

This past spring, for the first time ever, a Bates class traveled to Cuba. The island nation, cloaked in contradiction, hype, and stereotype, turned out to be a perfect liberal-arts laboratory, a place that motivated students to question assumptions that, for the most part, they had casually accepted until now.

I am a historian. My own research focuses on Cuba, and I have traveled there twice in the past year to do research. Last fall, after President Clinton signed new U.S. travel regulations permitting university-sponsored programs to be licensed for travel to Cuba, a colleague and I began organizing a Short Term class that would travel there in May.

Seventeen students signed up for the course (including one from Bowdoin). Prior to our trip, we spent two weeks at Bates doing background study on the Cuban Revolution. We then traveled to Cuba for two weeks and returned to Bates for the final week of Short Term. With our trip to Cuba, Bates became one of only a handful of U.S. colleges and universities sponsoring programs to Cuba. (Other institutions include Drake, Johns Hopkins, and Tulane universities.) The course gave Bates students a rare opportunity to experience firsthand a society and culture that has been forbidden to most U.S. citizens for many years.

Our itinerary included meetings with representatives of official as well as nongovernmental Cuban organizations. But perhaps the most illuminating conversations were with ordinary people on the street. They readily shared their opinions on Cuba and the challenges the country faces, especially in the current "Special Period," which is what Cubans call the economic crisis triggered by the fall of the Soviet bloc and the loss of Soviet aid and trade.

Even for an academic, Cuba can be a contradictory, confusing place. It doesn't fit neatly into familiar categories. Most Cubans are highly nationalistic, and resent the control that the United States exercised in their country prior to the 1959 Revolution. A majority also espouse strong support for socialism and for their Revolution. Yet at the same time, most are also quite open in discussing the problems facing their country and in criticizing their government -- as in most other parts of the world, including the United States, criticism of one's government and/or its policies is not considered rejection of or opposition to the country's political system.

While most Cubans are outspoken in their opposition to U.S. policy towards their nation, they also welcome visitors from the United States and are fascinated by U.S. society and culture. The Bates students were struck by the openness in Cuban society toward Americans, in contrast to the anti-American sentiment that one can encounter in other Latin American countries. Everybody talked to them; everybody told them stories and expressed opinions that made them constantly break down their preconceptions and stereotypes. One telling student comment was made early on in the trip: "It's so confusing here -- it's not just that things are not black and white, but really, nothing is even gray!"

As a teacher, it was amazing to see seventeen students become obsessed with trying to understand the Cuban Revolution. They sat up talking until two, three, and sometimes seven o'clock in the morning, trying to figure things out. The following quotes, excerpted from their final papers, show some of this process.

My family was the first to offer their ideas and everyone had something to say about what my trip would be like.... The first assumption was that the people I would meet would be very hostile towards individuals from the United States.The Cubans would be out to cheat and steal from you.Visitors to Cuba are often surprised when Cuban society fails to mirror their expectations. The Bates students were caught off-guard by their welcome, and that was the first step towards rethinking their perceptions of Cuba."You're going to Cuba? Wow, that's cool but aren't you a little worried?" "Don't they hate Americans there? You'll probably get arrested and put in some dark jail and be forgotten about." These are the types of responses I received when I informed people of my Short Term plans. I have to admit, I wasn't really worried at first but all those responses were starting to make me wonder.

There were no resentful feelings towards me because of my country's politics. I was seen as an individual, not reflective of my country's actions.... There never seemed to be hostility or unfriendly words to us as North Americans.The students were particularly struck by Cubans' willingness to discuss the problems that their country is facing.

I expected [two Cuban acquaintances], as party members, to be an endless well of party propaganda. In contrast, however, they spoke freely of the sacrifices preserving socialism has meant for Cuba and their family, but were also critical of how politics has many times floundered in its attempts to improve life and liberty for the Cuban people.There circulates much criticism in Cuba, both by intellectuals and nonintellectuals, of the Revolution as well as of Fidel Castro's policies, yet most of this occurs within the bounds of socialism.... The average Cuban, whether a supporter of the Revolution or a critic of it (two classifications that are definitely not mutually exclusive) is informed of current events, and has an opinion.

![[Photo: a 1950s automobile]](cuba.photo2.jpg)

Above: a 1950s automobile hints at pre-Revolution Cuba.

These changes have contributed to an economic recovery in per capita terms, but they have also contributed to a growing inequality among Cubans that threatens the egalitarian ideology of the Revolution. There is, for example, jineterismo (from a Spanish word for prostitute), a word that describes the scrambling, peripheral efforts of some Cubans to attain U.S. dollars, through black-market activities, independent taxi services, begging, prostitution, and other tourist-related activities.

By supporting the dollar and the industries of jineterismo and tourism to bring in the dollar, Cuba has not only threatened national pride but also the moralistic code that was so deeply rooted in the Revolution.Most of the students were also exposed to the realities of U.S. foreign policy in ways that they had never been before. They were shocked not only by the impact of U.S. policy in Cuba, but at their own previous ignorance of it, especially the recent Helms-Burton Act, which tightens the international screws on Cuba. If the Cubans they met expressed a wide variety of opinions on socialism, the Revolution, and Cuba's future, there was a virtual unanimity in their opposition to current U.S. policy.Cuba's commitment to health care, education, and curing hunger are impressive compared to Latin American, Third World, and even First World standards. Everything from annual checkups to heart transplants are free to Cubans. As one doctor from Havana explained..."We [doctors] would be sinners if we refused to treat someone based on their income. The only way we can help everyone to be healthy is to take out the monetary value of health. That only creates tension and hatred."

The recent surge in the dollar... [and] the creation of such establishments as "El Rápido," a fast-food restaurant conspicuously decorated in an otherwise bland environment, Cuba may be on the verge of a "McDonaldization" of its own, where the dollar and a "quick buck" is valued over revolutionary concepts of morality and solidarity.

After having visited hospitals and with citizens of Cuba, I have seen what [the U.S. embargo] means to the public. It means that AIDS patients are dying because of a medicine which is only produced in the U.S. and is unable to get to the dying patients. It means that what Americans take for granted are luxuries for Cubans.The students were also exposed to other aspects of the power of the United States in the world, and their own privileged position in the so-called "new world order." They found themselves trying to explain to Cubans that the reality of the United States is much more complex than many Cubans believed.

No matter how liberal one's ideals may be, often times appearances speak louder than words. For example, I often found myself ... attempting to convince [a Cuban] of the existence of a large, economically marginalized portion of the United States. Yet no matter what I said, the fact was that I stood before them as someone who had traveled outside of her own country, with my fancy camera, new sneakers, having never experienced a blackout, or a shortage of water, let alone being hungry. In this respect, I was just more proof of the U.S.'s opulence.Alejandro, a cook who had a brother and an aunt living in Miami ..., said even though they were not doing well financially he would love to join them. If given the chance he would love to leave Cuba. I brought up the fact that there is no free health care or education in the United States. He said the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. Despite working, he doesn't have enough money for food, clothes, shoes or any luxuries. To go to this club we were at cost him half a month's salary. That is why he dabbles in the black market.... He had an idealistic vision of the capitalist United States, that hard work would pay off and he could buy what he wanted.

![[Photo: Cuban cigar production]](cuba.photo3.jpg)

Above: students saw the legendary Cuban cigars being hand-made, but when they tried to bring cigars legally into the States, U.S. Customs confiscated the product.

A student who was carrying some prescription medications (in their original bottles, clearly labeled) had the most traumatic experience. An official examined each bottle and questioned her about the contents. "Why do you take Prozac?" he asked. "For depression," she answered. "How old are you?" he asked. "Nineteen," she answered. "You can't be depressed if you're only nineteen," he told her. She also had some other medications for migraines and for menstrual cramps. After examining and questioning her about all of them he said, "You must have the body of a forty-year-old. At least you have the medicine cabinet of a forty-year-old." At the end he said, "Good girl, now you can go." The student left in tears.

The students were bewildered by the customs experience. They kept asking questions like, "Are they really allowed to do this?" By the end, they seemed to have figured out that it was irrelevant whether they were "allowed" to do it or not. Indeed, nothing the customs officials did was illegal, such as confiscating items such as cigars and ceramic, wood, and bamboo artisanry, even though it is legal to bring those items into the United States. I'm not sure to what extent the students were able to see their experience in the context of the resentment they heard Cubans express about U.S. policies towards the island.

![[Photo: mural of Che Guerava]](cuba.photo4.jpg)

All Rights Reserved.

Last modified: 12/12/96 by RLP