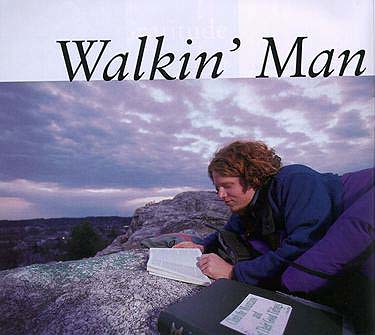

Story and photo by Marc Glass '88

Ryan Williamson '01 would argue that Wordsworth got it right: "The world is too much with us; late and soon, Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers: Little we see in Nature that is ours...." From sport-utility vehicles whose girth, ground clearance, and heated seats promise to insulate us from both potholes and natural disasters, to cell phones that keep us safely tethered to people, pavement, and the neighborhood pizzeria, the evidence is undeniable: we work hard to defy the ascetic impulse. Not Williamson. On this mid-February eve in Lewiston, it's at least 10 degrees below zero, and as he has done almost every night since coming to Bates in September 1997, Williamson is sleeping outside. Tonight, he's sans tent but is using a down sleeping bag and wearing a polarfleece pullover and overalls he sewed for himself. The television meteorologists are screaming about wind chill, but Williamson isn't afraid of the cold. He knows the signs of hypothermia's onset because he has deliberately placed himself in real danger of freezing just to make sure he knows the limit. Tonight, he says, he's not even close. "When you look at how much people invest of themselves in cars and houses and clothes, you can tell that people are afraid of being exposed to the environment. They lock themselves out of it," Williamson said. "We carry our insecurities with us when we venture outside, and that's why I like to go light. I do have a fear of being really cold, but bad weather can be the most beautiful weather." Williamson is reluctant to reveal that his favorite place to sleep in Lewiston is atop Mount David. Well-meaning campus security officers have chased him away from here before, and he doesn't want to appear to be thumbing his nose at them. Here, in fall and spring, he often forgoes bag and blanket for sleeping on the ground under a debris shelter, a handmade lattice of leaves and boughs he drapes over his body. Despite behavior that may be out of step with his classmates (not to mention the rest of society), Williamson is really more Johnny Appleseed than High Plains Drifter. Sort of Henry David Thoreau meets Ben Franklin. An entrepreneurial designer of fleece clothing, he's got his own wholesale company with clients that include the Bates College Store. A self-taught photographer, he creates prints that have none of the amateur's awkward self-consciousness. And as part of a Short Term sojourn down the Appalachian Trail, he's stopping by public libraries with e-mail access (gotakeawalk@yahoo.com) to file diary entries with Short Term teacher Gary Lawless, instructor in English, as well as a long list of friends from Bates and abroad, including award-winning author and Western naturalist Terry Tempest Williams, who delivered the Philip J. Otis Lecture at Bates in October 1998. How did Williamson, raised in Crozet, Va., around the mountains of Shenandoah National Forest, with his devotion to mountains and disdain for all things urban, come to Bates? The first day of summer vacation after his junior year in high school, Williamson set out to walk the Appalachian Trail from Virginia to Maine's Mount Katahdin. (He's walked most of the AT three times and 750 miles of the Pacific Coast Trail, too.) He finished the trek two days before the start of his senior year and - based in large part on the beauty of the Mahoosuc mountain range and the rest of the northern AT - decided he would get his mortarboard in Maine. Though he never visited Bates, Williamson was sold on its stellar academic reputation. He anticipated living in a foothills town - ideal for restorative weekend getaways and, of course, comfortable alfresco sleeping. Williamson said he was initially surprised by the College's relatively urban environs, but quickly discovered its outdoor possibilities, even at night. He learned to seek high spots in the evening, craving the absence of noise and light pollution. From Mount David and some campus rooftops, the wind chases out the sounds of traffic, and street lamps don't compete with the stars. Besides, his room back in Nash House, recently renovated and earmarked for students dedicated to environmentally conscious living, is far too hot and stuffy for good sleeping at 70 degrees. When he's not sleeping outside or confined to a classroom, he walks around Lewiston, often stopping to forage either a healthy snack (rose hips, various berries, burdock, mushrooms, and echinacea, among others) or the raw materials for a project (milkweed to be hand spun into twine, or an old bicycle pulled from the edge of the Androscoggin River to be fixed up and given to a person who needs free transportation). "It's amazing what's around here that no one pays attention to," said Williamson, as he munched some rose hips for a dose of vitamin C. "One of the primary ways to know your environment is to eat and work with what's available." Williamson found an opportunity to work with what's available in his "Wetland Science and Policy" course with Curtis Bohlen, assistant professor of environmental science. After writing a paper on how native communities use cattails for baskets, toys, and medicinal purposes, Williamson tried many of the uses described in his references - even recovering minuscule roasted cattail seeds by burning the flowering heads and making small dolls out of the plant's partially dried leaves. "Not too many students focus on that kind of hands-on research. It's a style of learning that isn't always encouraged," Bohlen said. "I attribute his willingness to find his own way to home schooling. Without a curriculum, he's used to having his own interest be the measure of significance for what he's working on." Before dismissing Williamson as a carefree nature boy, it's important to understand how his upbringing in rural Virginia shaped his decision to lead what he calls a "conscious life," valuing time over money, respecting the environment in his endeavors, and traveling light. Williamson's parents provided no material luxuries, out of economic necessity and a desire to encourage a sense of industry in Ryan, his brother, Nathan, and sister, Rachel. "Their philosophy was that if we wanted something, we would have to figure out how to make it or make something else of value, sell it, and purchase what we wanted with the profit," said Williamson of his wood-turning father, Fred, and his mother, Jacque, who now is a professor of education at Southern Connecticut State University. "My father didn't make much money, but he wasn't chained to the nine-to-five day. He and my mother had time for us." Williamson, home-schooled by his parents until he was 14, made potholders at age 5, grape-vine wreaths at age 7, hand-carved signs at age 9, and hand-made knives at age 11. He sold his wares at craft fairs and folded the profits into what every kid wants - mounds of hiking gear as well as chemistry sets. At 14, Williamson stitched a jester hat out of fleece, wore it to Western Albermarle High School the next day, and was offered money for it by several of his peers.

People liked what they saw; he sold 1,400 hats during his senior year of high school. Now chief financial officer, senior designer, and head stitcher of his one-man fleece-wear company, The Mouse Works, Williamson takes stock orders in April from retail stores in the South, including the 15-store chain of Blue Ridge Mountain Sports. His fleece hats, pullovers, and overalls are also available in the Bates Bookstore, and his "Snowdrop" hat can be seen on the store's online catalog at www.bates.edu/admin/offices/collegestore/catalog/page1.html

"Ryan made his first hat delivery in true Ryan style - in a large trash bag that he

encouraged us to reuse," said Sarah Potter '77, director of the Bates College Store. "A

'business' meeting with him inevitably leads to other discussions, always enlightening,

about recycling, siblings, liberal arts, South Africa. He has been one of those job benefits

we so often get here at Bates - a thoughtful, interesting student, pursuing his own course

with determination and sharing that pursuit with some of us lucky observers." How does Williamson reconcile his business success with his quiet rejection of materialism? "I guess it's the lessons of my parents' philosophy. I stitch and sell fleece to pay for college and whatever gear I can't make myself that I need for long walks," said Williamson, whose skill at the sewing machine can be seen in the Gore-Tex pants, synthetic-down parkas, backpacks, and even a wetsuit he has made for himself. "Right now I need to sell a couple pairs of overalls so I can buy the shoes I'm going to walk home in." Williamson doesn't wear much on his sleeve, regardless of whether he made the shirt or scrounged it from the Salvation Army. When asked what his peers think of him, Williamson admits there isn't much understanding of a guy who refurbishes junk from the Androscoggin or finds a snack from crabapple bushes outside Carnegie Science. He might as well be Thoreau sauntering around Concord to the amusement of his neighbors. That's OK with Williamson, whose motto - if he were bold enough to have one - would be, "Let it be." Except there are some things he can't let alone. Seeing recyclables going unrecycled is an affront to Williamson. About a year ago, he noticed few recycling bins for paper products in the Dining Services work areas and waged a campaign of education with Commons employees, meeting informally with them to explain what among their paper products could be recycled. Finding a receptive audience, Ryan secured more recycling bins, personally delivered them to Commons and produced signage to direct workers about what mixed-paper products could be recycled. (In May, Dining Services was honored for best practices that encourage environmental sustainability by the National Awards Council for Environmental Sustainability and the President's Council on Sustainable Development.) "The beauty of Ryan's project lies not only in the fact that the amount of trash has been cut in half, but also in the relationships he fostered along the way," said Maria Libby, environmental coordinator at Bates. "He opened an avenue of communication that typically doesn't exist between students and staff. When he walks into Commons for lunch, he is greeted from every angle by name and with a warm smile. Ryan effected change and the rewards were tremendous."

As he strode south on Campus Avenue, bound for his first night of rest just outside of Freeport, he realized he still had his keys in his pocket - keys to the room in which he never slept at Bates. He chuckled to himself as he lightly tossed them in his hand and asked that they be returned to Physical Plant. Was he at all frightened by the expanse of distance and uncertainty that lay ahead of him? "Naw," he replied with a grin. "Walkin's good for me."

|

|

©1999 Bates College All Rights Reserved Last Modified 7/28/99 by Ngan Dinh |

"I was from the woods, so I didn't know shit about colors and styles," said

Williamson, clearly amused by the recollection of how his classmates clamored over the

bags of fleece hats he brought to school. "All I had to do was see what people liked and

make more of that."

"I was from the woods, so I didn't know shit about colors and styles," said

Williamson, clearly amused by the recollection of how his classmates clamored over the

bags of fleece hats he brought to school. "All I had to do was see what people liked and

make more of that." Williamson stopped by the Bates Office of College Relations at 4 p.m. on April 21 to

drop off his best-guesstimate itinerary and bid farewell. His hand-made backpack was

loaded down with all manner of dried fruits and vegetables, maps, bagels, and hand-sewn

clothing. (He also had his father mail his driver's license from home, as he expected some

police scrutiny while walking through some of southern New England's more genteel

towns.) He had sold enough fleecewear to buy his walking shoes, but his greater source of

pride was having found a somewhat homely, but nonetheless functional cast-off umbrella,

which he rigged to the shoulder strap of his pack to keep the rain and sun off his copper

curls.

Williamson stopped by the Bates Office of College Relations at 4 p.m. on April 21 to

drop off his best-guesstimate itinerary and bid farewell. His hand-made backpack was

loaded down with all manner of dried fruits and vegetables, maps, bagels, and hand-sewn

clothing. (He also had his father mail his driver's license from home, as he expected some

police scrutiny while walking through some of southern New England's more genteel

towns.) He had sold enough fleecewear to buy his walking shoes, but his greater source of

pride was having found a somewhat homely, but nonetheless functional cast-off umbrella,

which he rigged to the shoulder strap of his pack to keep the rain and sun off his copper

curls.