The church struggled to scrape by. Paper curtains covered the windows. Folding metal chairs served as pews. In winter, members huddled around the stove. There was no choir or music director, and sometimes no one to play the old, upright piano. But the congregation sang from the heart. Women kept up a constant, moaning chant as the minister's singsong preaching crescendoed. Those touched by the spirit shouted and danced.

"Being with other black people," Buckley says, "and sharing in the music of my heritage was of the utmost importance."

Buckley brings the same heartfelt spontaneity that she learned as a child to her gospel singing these days at events such as a Sunday gospel brunch at Morganfield's in Portland, the Portsmouth Blues Festival, and a recent show at Berwick Academy.

She performed recently at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration in Portsmouth and at the University of New Hampshire.

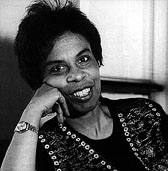

Never formally trained, Buckley has developed her own striking style. Her voice sinks to low groans, soars with power, cries out in anguish. "Her passion comes through loud and clear," says T.J. Wheeler, a blues musician from Hampton Falls, New Hampshire, and executive director of the Blues Bank Collective. "It's just really clear that she's tuned into a higher power through her music."

Buckley, thirty-seven, recently began writing and performing her own songs. She also works at the postal service, and she's studying for the ministry.

Though best known as a performer in New Hampshire's seacoast area, Buckley has lived nearly all of her life in southern Maine. She grew up in Kittery, the youngest of four children. After living on her own for several years, she now shares a home in Kittery with her parents and her brother, Chester. She is five-feet-two, slim, with short, brown hair.

Music, religion, and the experience of growing up black in a mostly white environment have shaped Buckley's life since she was a child. From infancy through grade school, Buckley attended Faith Mission with her mother and Chester, who is the closest to her in age of her three brothers. The mission was affiliated with the Church of God in Christ.

Chester loved to sing. And he was bolder than his sister. When Lillian was about eight, they began performing together for the church. Lillian had to summon her courage to stand in front of the congregation. But her voice harmonized easily with Chester's on the old hymns. "I got lost in the music," she says, "and I kind of opened up."

Urban renewal forced Faith Mission to close in the late 1960s. Lillian moved to her father's congregation, Peoples Baptist Church (now called New Hope Baptist Church) in Portsmouth, which also was made up mostly of African Americans. At age eleven, Lillian went up to the altar during a revival service and, she said, accepted the Lord as her savior.

Lillian and Chester joined the church choir. They sang without sheet music, improvising parts as they went along. Every Sunday, she remembers, "We just sang our guts out."

Lillian and Chester continued to perform duets at church. They also sang at First Parish Church in Portland for Kenneth Curtis, then the governor of Maine.

Outside of church, Buckley excelled at just about everything she tried -- except piano. ("I didn't practice," she confesses. "I'm lousy at it.")

An honor student at Traip Academy in Kittery, she sang in the school choir and played three varsity sports -- basketball, field hockey, and softball. Still, she felt subtle discrimination as the only African American girl in her class. "I never dated," she said. "I was popular. I was a scholar-athlete. Nobody ever asked me out. I still haven't gotten over that."

Buckley graduated from Bates in 1981 and joined the U.S. Postal Service two years later. She worked her way up from letter carrier to postmaster for the town of Eliot, a job that put her in charge of twelve employees.

Buckley continued to perform. She sang for several years with a Christian rock band. She teamed up with another woman to create a gospel act, Amazing Grace, that played for weddings and concerts. She also performed contemporary Christian music with a musician from Concord, New Hampshire.

But all of those partnerships ended because of differences over money and music or simply in personality. Buckley was so discouraged that in 1989 she finally told herself, "No more singing...I'm just going to sing in the shower."

At home, Chester was suffering from schizophrenia. He was hospitalized three times at the Augusta Mental Health Institute.

Friends deserted the family, which Buckley says left them with a feeling of isolation. "It was like a death, but he didn't die," she said. "I stopped even listening to music at all, even the radio. I didn't even sing in the house."

In her darkest hours, Buckley found that she could only share her pain with God. She decided then to become a minister, so that she someday could bond with others when they too were suffering.

In 1990, Buckley enrolled in Harvard Divinity School as a part-time student. She joined the school's choir, and soon became a star performer.

Buckley gave a solo performance of an old hymn, "Blessed Assurance," at one divinity school concert. She sang it in a "slow, mesmerizing, gospel style that almost literally brought the house down," said Ruth S. Roper, then the choir director.

"She can go from very soft to very loud, and inflect her voice in a way which just sends goose bumps up and down the spine and opens hearts up," said Roper. "That's something you either have or don't have -- it can't be taught."

Without thinking about it, Buckley had found a way to use her pain in her singing. And it was reaching others.

About a year and a half ago, Buckley began waking in the night with ideas for songs. They, too, tap into the pain she has experienced, and the pain that African Americans have suffered for generations. Kent Allyn, a York musician, helped her arrange the songs. When she performs, he sometimes accompanies her on keyboard and guitar.

Buckley plans to record some of her songs on a CD as part of her divinity school thesis, Utterance. The songs center on pain, she says. As part of her studies, she volunteers two nights a week at a Portsmouth battered-women's shelter. She did a previous internship in pastoral counseling at Maine Medical Center.

Buckley, who continues to work full-time for the postal service, expects to complete her graduate studies, "the good Lord's willing," in the spring of 1997. She then will seek ordination as a Baptist minister.

Buckley hopes eventually to combine work as a minister with writing and performing her own music.

"It would be lovely to know that more people got to hear her singing," said Roper, the former Harvard choir director. "I've always thought she was ready for prime time."

By Shoshana Hoose

Reprinted courtesy of the Maine Sunday Telegram.

All Rights Reserved.

Last modified: 7/25/96 by RLP