When Ozzie Jones tells you, "I loved Bates," know that he really means it. But know too that such a love was not easily come by.

That's a fact familiar to those who witnessed the bright streak Jones blazed across the

Batesian firmament a decade ago. They'll tell you that yes, sometimes, his easy charm was

needed to sweeten a confrontational style of making things happen. But they'll also agree

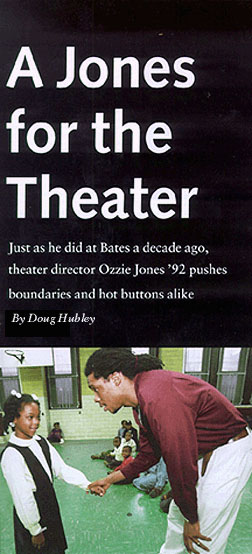

that when Ozzie Jones went over the top, he generally had a reason. "We functioned as social directors, in some ways, for the whole campus," he recalls. As the parties got more popular, "they turned more and more into plays. The line got murkier between the party and the play." At the same time, what got clearer was Jones' talent for directing, sharpened by coursework that turned him into a theater major. Today, although he tours and records with a rap band named Name, it's theatrical work that has made Jones a hot ticket in Philadelphia, his home town. And beyond, for in August, Jones became artistic director for the historic Lincoln Theatre in Washington, D.C. His 1999-2000 season there includes Langston Hughes' Black Nativity, for which Jones won a major directing award a few years back, and Sanctified Jook Joint, his adaptation of Zora Neale Hurston's Sanctified Church. Jones may be best known for a 1997 adaptation of Othello that ran for a month in Dublin, Cork, and Galway. This Second Age Theatre Company production made Jones the first African American to direct an Irish company in Ireland. It also very possibly made Michael Grennell the first Irish actor to portray Othello in blackface - which they had to bring in from the States, it being unavailable in Ireland. And why, after all, should an all-white land like the Emerald Isle need to be troubling itself about such things? For Jones, it's little symbols like that, thrown up to us by life, that are the key to revealing the great social forces beneath. Consider hair. In Ozzie Jones's time, there was no haircutter near Bates who understood how to cut an African American's hair. "We shouldn't all be sitting in a room cutting each other's hair at a school that costs" as much as Bates, Jones says (although he was pleased to spot a black hair-care salon in the neighborhood on a recent return visit). So when Jones tells you, "I loved Bates," know that he really means it. But know too that such a love was not easily come by. Late one September morning the 29-year-old Jones is talking about Bates, his work and what the one has to do with the other. He's on the phone from the North Philadelphia apartment that he shares with his wife, dancer Lisa White Jones, and their 3-year-old, Arvelle C. Toussaint Jones III. Jones keeps yawning. He was up late the night before, working on a film script in a class with inmates at the 1,100-bed State Correctional Institution in Chester, Pa. Jones does not separate doing good from doing well. Social issues figure in his work, and his work is done out in the community as often as on stage. "I don't really see art as being something that only happens in the head of the artist and is relevant only with respect to that," he says. "It has to have some concrete reality." Concrete reality, indeed. Jones grew up in the same black Philadelphia neighborhood that produced rapper-movie star Will Smith (yes, they knew each other). Ozzie's mother, Esther Mae Jones, was a teacher, now retired. His father, the Rev. Arvelle C. Jones Sr., is a CPA, erstwhile city administrator, and lifelong scholar with a string of degrees to his credit. Mrs. and the Rev. Jones raised Ozzie and his sister, Crystal, on a foundation of bedrock beliefs - in God (Ozzie is a devout Baptist), in knowing your mind and speaking it well, in seeing strangers as friends until there's reason to think otherwise. Jones admits, with some embarrassment, that he was drawn to Bates in part because the campus looked so pretty in the brochure. Once here, though, he was not given to swooning under the trees in an academic reverie. Instead, he was making himself heard however possible. Protesting a South African boxer's local bout. Joining the debate team. Deejaying at parties. Turning heads with his guitar and piano work. A production of A Raisin in the Sun opened Jones's eyes to the political potential of the stage. It was the first Bates production by a new lecturer in the theater department, a performance artist with a baffling name. William Pope.L was told, on the one hand, that he should do a piece with an African-American angle; and on the other, not to expect a big turnout of black actors. He responded by rewriting Lorraine Hansberry's classic to expose the awkward realities of the present situation. The tactic "was a huge influence," Jones says. He ate it up - Pope.L's bold use of text, blocking, acting, and, in particular, the cross-racial casting that included a white actress in a giant "mammy dress." (With the Irish Othello, Jones would strike his own telling blows through cross-casting. His stunning concept of the blackfaced Othello turned the general into a "minstrel," the symbol of a black man built to white specs and doomed because of it.) As playwright, director, and actor, Jones pushed boundaries and hot buttons alike at Bates. "People thought he was brilliant," says Pope.L. "People thought he was a troublemaker. People thought he wasn't living up to his potential." But everyone agreed, of course, that Jones was certainly charming. Jones always went for laughs, and often the intent was charming. Smokin' Hamlet and 24 Hours, which Jones cooked up with Eliot King Smith '91, assembled on stage a group of "actors" whose sole direction was to sit on stage and interact for the next 24 hours with whomever was around. The point of the piece - aside from raising several thousand dollars to pay for an appearance by Angela Davis - was to challenge the bystanders to make their own theater.

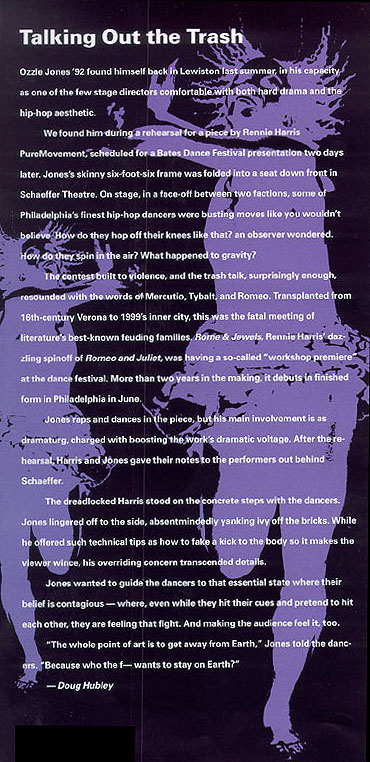

"Ozzie would just take it too far," laughs Norman Williams Jr. '91, a public defense lawyer for the city of New York. He and Jones have been close friends since Bates. Jones, he says, "always looked to wrestle with controversial issues - racism, sexism, typical campus life. I guess he would just give a black perspective in an extremely, extremely white world, and whether truthful or not, sometimes people just couldn't take the strength of his message." According to 1998 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau, Maine's black population of 6,321 is the nation's sixth smallest overall and, at .5 percent, smallest altogether as a percentage of the total population. At Bates, Jones was one of 32 black students in his first year, about 2 percent of the campus population. In terms of racial tolerance, says Williams, Bates "was far from the worst, but it was what it was. It was a small campus in New England, and New England's minority culture isn't the strongest in the world. A lot of the students at the school never knew a black person personally - they only knew black people as far as they saw them on TV." A popular figure on a generally open campus, Jones himself suffered few instances of outright hostility based on race, although he was quick to respond when others fared worse. What grief blacks and other minorities tend to encounter at colleges like Bates, observers agree, tends to arise more from ignorance or inexperience than maliciousness. Alcohol had a lot to do with it. Some drunk at a party would single out the sole black person to ask why this black athlete did this or that black politician said that. An amorous advance made under the influence, in what Jones describes as a "weird zoological experiment," would revert to "keep your distance" the next day. Even at schools, like Bates, that devote considerable thought and resources to creating a supportive environment for minorities, that process can seem much too slow when the day-to-day whiteness of the world is so overriding. It's somewhat easier for kids accustomed to being the only different ones in a school or a neighborhood. It's harder when you come from all-black neighborhoods, as did Jones, Williams, and many others in those days and today. Bringing in black speakers and artists is important, but even these programs can seem like window dressing. "When the program is over and you go home at night, you still feel like you're visiting," says James Reese, in his twenty-third year as associate dean of students. "And that's what Ozzie felt." Amandla! helped. The union not only brought cultural notables to campus but lobbied effectively for stronger recruiting of black students and faculty. It didn't hurt that this period of activism coincided with the arrival of President Harward, a vigorous proponent of campus diversity. There were other refuges from the long, cold Maine winters. Dean Reese opened his home to Jones and friends. A night owl himself, Reese says, "I could go to bed at one o'clock and not be surprised at 1:30 to hear banging on my door, loud. And I would go down and let Ozzie in." The late Robert Branham, Bates' beloved professor of rhetoric and director of the Quimby Debate Society, was a good friend and powerful influence, instilling in Jones the thinking person's responsibility for his or her thoughts and the importance of rendering thought into action. And Celeste Branham, dean of students, remains one of Jones' favorite people at Bates. The feeling is mutual, despite the fact that their earliest encounters were generally driven by Jones's grievances. "He's just a joy," says the dean. "He's infectious in terms of his humor and energy and good will." Jones graduated with high honors, and quickly found similar success in the musical and theatrical worlds. His list of theater credits is impressive, from a spot on Lincoln Center Theatre's 1995 Top 100 list of young American directors to his recent collaboration with the Rennie Harris PureMovement dance company on an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet Jones, as you may have gathered, isn't much concerned with light comedy, mainstream realism, or the theater of the abstruse. "Anything where man is trying to work out his relationship to God and to the world, I'm interested in," he explains. Which isn't to say that the years have turned him somber. On the surface, Jones says, his pieces continue the traditions of black vaudeville, the blue-collar plays of the "chitlin circuit," black musical performance, and the church. The heavy stuff sneaks up on you.

Jones has no interest in being a crossover director. "I'm affected by and love everything, but the only way I'm interested in telling the story is with black people," he says. He sees a parallel with the film director Kurosawa, who adapted, through the lens of Japanese culture, stories from sources as diverse as Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, and police-thriller author Ed McBain. For Jones, it's the likes of James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, James Joyce, Ntozake Shange, William Shakespeare, and William Butler Yeats. Jones is reluctant to discuss his goals. He says, "The answer gets really big sometimes." As in directing feature films, recording albums that go platinum, winning a Grammy, winning an Oscar. Pressed, he allows that he wants to earn enough money to be able to pick and choose his projects and, more important, to be able to boost his family another rung up the economic ladder, as his parents did for him and Crystal. Something he learned at Bates still serves him well in that regard. "In America, if you want to be successful, particularly if you're black, you've got to understand where people's racism may be coming from," Jones says. That is, you have to do their thinking for them. "And also to learn that just because you meet racism, it doesn't mean that you can't get what you need done, done. That was an enormously helpful lesson to learn. "There's nothing, I think, for building up the mettle of a black person like having to succeed in an all-white situation."

Doug Hubley is a writer and musician. He lives in Portland, Maine.

|

|

©2000 Bates College All Rights Reserved Last Modified 4/27/00 by Ngan Dinh |

Sometimes the charm was less evident. Deconstruction of Rhythm, a sprawling satire he

wrote in his junior year, seriously polarized its audience and netted Jones some heavy

criticism. A harshly comic view of race relations (among other things), Deconstruction's

symbolic arsenal included a five-foot, jet-black papier mache phallus. That play, says Jones,

"was definitely done out of anger."

Sometimes the charm was less evident. Deconstruction of Rhythm, a sprawling satire he

wrote in his junior year, seriously polarized its audience and netted Jones some heavy

criticism. A harshly comic view of race relations (among other things), Deconstruction's

symbolic arsenal included a five-foot, jet-black papier mache phallus. That play, says Jones,

"was definitely done out of anger." "When you come to one of my plays, you can dance, you can sing, you can talk out loud to

the stage," he continues. "For me, the trick is to get you to feel like that, while at the same

time encoding all the aesthetic stuff under that, so you don't really think about that until

much later."

"When you come to one of my plays, you can dance, you can sing, you can talk out loud to

the stage," he continues. "For me, the trick is to get you to feel like that, while at the same

time encoding all the aesthetic stuff under that, so you don't really think about that until

much later."