![]()

By TANIA RALLI

Arts Editor

Staying somewhat in tune with Bates' previous exhibition of body conscious

art, Panzera, a professor at Hunter College, City University New York,

introduced his work with a lecture and slide show to a small audience of 40

people. Dressed conservatively in a suit jacket and tie, Panzera talked about

his art and how it is that he arrived at producing the life-size drawings now

being exhibited in the upper gallery of the Olin Arts Center.

Staying somewhat in tune with Bates' previous exhibition of body conscious

art, Panzera, a professor at Hunter College, City University New York,

introduced his work with a lecture and slide show to a small audience of 40

people. Dressed conservatively in a suit jacket and tie, Panzera talked about

his art and how it is that he arrived at producing the life-size drawings now

being exhibited in the upper gallery of the Olin Arts Center.

Panzera conducted an independent study in Florence, Italy, just over 20 years ago focusing on Renaissance art. He was inspired to fresco his own studio and received a grant to do so in 1991. In preparation for the wall drawing, he produced a lifesize cartoon (preparatory drawing for a fresco) of a man and a woman. With an appreciation for the effect of the cartoon, he began to display his drawings in the large final format.

Panzera joked, "Frescoes were not meant to travel," as he turned the last minutes of his talk to the 15 pieces displayed in the museum. With the exception of three narrative scrolls, the works appear as figure studies. The artist says that his "investigation of the human figure is not only anatomical, but spiritual."

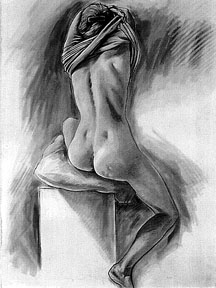

However, this alleged spirituality is difficult to see considering that many of the models' faces are obscured, giving us no insight to their expressions or moods. Take, for starters, the pictured drawing from the "Hibernia Series" entitled "Woman Dressing." She does not appear to be dressing, but rather actively undressing. Yet this depiction is not as problematic as Panzera's narrative scroll drawings.

The first scroll depicts the story of "Leda and the Swan," based on the version of Yeats' bestial poem by the same title. According to the scroll Leda weakly resists Zeus mascarading as a swan while he overpowers her. The end result is a picture of a woman raped and discarded.

Hanging underneath "Leda and the Swan" is a scroll of the same size which symbolically wants to convey an impression of "The Arabian Nights." To begin with, the choice of this story by the artist is questionable because it sympathizes with a cuckolded king that resolves to sleep with a different woman each night and have her killed the following morning.

One maiden, with the intention of saving the women of the kingdom, has sex with the king and manages to ward off death night after night by telling compelling, never-ending stories. One thousand and one nights and three kids later, the king "having learned to trust and love her, spared her life and kept her as his queen." How terribly gracious.

Turning to the actual scroll makes matters worse because it takes away from the woman' s potential role as a heroine and reinforces the despotic nature of the nights. The scroll lacks any sort of narrative quality and represents the same figure in eight compromising positions. Each pose totally obscures her head, and resultingly eliminates her identity. Visually presenting a woman seemingly void of personality enforces the mysogyny of the story. Two of the figures in particular render the woman lying on her back, helpless.

Apparently Panzera is fond of hiding the faces of his female models because this theme continues in a scroll drawing entitled "Six Views of Mia." In an explanation of the series, Panzera writes that the topic is "a playful interplay between the model, the drape and my dog Mia." The scroll intends to focus on the dog but this is difficult to do when three different bodies are strewn in the background.

The first model in "Six Views of Mia" lies in an awkward, facedown position. Her face is turned away and a limp arm hangs to her side. The wrist of the second woman rests in a sling fashioned out of the drape that deliberately hangs so that it hids her face. Unsurprisingly, the drape is specifically fastened to hide the face of the third woman and is hardly "playful," though Panzera tries to disclaim his dipiction by writing, "the anonymity of the model shifts the focus to the dog, so that her view of the world is central to the vignette." But the women do not blend into the background as intended because they look so blatantly uncomfortable.

Museum curators brought Panzera to Bates because he seems to fit some idea of

the academic tradition with a link to the art of the Italian Renaissance, said

Genetta McLean, director of the museum. While his drawings may exhibit an

amount of technical skill, Panzera's lack of morality and sensitivity regarding

the selection of narratives is inexcusable. Panzera needs to get the big

picture.

Last Modified: 11/5/97

Questions? Comments? Mail us.